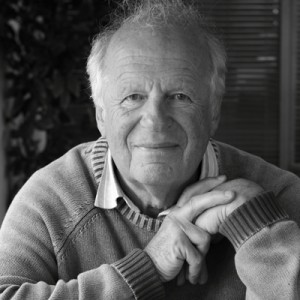

Robin Mills went to West Bay, Dorset, to meet Arthur Watson. This is his story.

I’ve been in West Bay for quite a long time, now. I was born in 1936, in Surrey, and in 1939 at the outbreak of war, my father, and I’ve never been too clear exactly why, chose West Bay as the place to which my mother, sister and I were evacuated, and we arrived in 1939.

For a while we lived in the old coastguard cottages on East Cliff, and then a house came up on West Cliff, which my parents managed to buy, and I lived there from the age of 3 until I was about 20. Perhaps it should have been an idyllic place for a boy to grow up, but the war was ever present. The Army was here, and the Navy, there were tank traps and barbed wire, and you needed passes to move around. So there were a lot of restrictions, and life was quite difficult, the main problem being there were few other children around. Once, a highly secret Heinkel aircraft came down by West Cliff; the German crew were completely disorientated, thinking they were in northern Spain, and crash-landed on the beach. The pilot was killed, but the crew sought help from the locals, thinking they’d get a reasonably friendly reception, only to get arrested. The crashed plane was cordoned off by the Home Guard, and when officials arrived to investigate the plane’s sophisticated, secret anti-radar equipment, in true Dad’s Army style they were refused access because they didn’t have the proper documents. By the time three successive tides had washed back and forth over the plane, there was nothing left to investigate. That was the story, anyway.

The American Army came in 1944, taking over most of the houses, but because my father was in the Navy they didn’t requisition ours. Then we had the time of our lives; the Americans all had families back home, and they treated us kids like we were their own. We rode on tanks, had chewing gum and bananas for the first time. West Bay was a quiet, gentle place to grow up. The cinemas, the Lyric and the Palace, showed wonderful films like Old Mother Riley and The Three Stooges, and war films of the day. I swam, and we all did daft and dangerous things like swimming across the harbour between the old stone piers. And I played water polo for Bridport—for many years the pitch was set up in the River Brit!

My mother was from Tiblisi in Georgia. My father must have met her when the British were sent, after Salonika where he’d fought, to Georgia to protect the oil pipeline from the Caspian to the Black Sea, and also to try to deal with the “descending Red Hordes”, the communist threat from northern Russia, which of course was a hopeless task. That must have been 1919 or 1920, and we never knew if they were married in Georgia or here, but she came back to England with him to live in Surrey in 1920. From their photos of the time, they had quite an exotic lifestyle; there were many expatriate Russians living in London at the time, Tsarists who’d fled to Paris and London. But not Bridport, as my mother found when she moved down here. Sadly, my father had got involved elsewhere and didn’t return, so my mother found herself very isolated, with two children and no means of earning a living. Her hurt meant she rarely mentioned my father again; he ceased to exist for her. This has always seemed to me to be a lesson for all of us; it’s important to find out as much as possible about one’s parents while they’re around because after they’ve gone, the family stories go with them.

For a while my mother worked at Gundry’s in Bridport with a French friend, making camouflage nets. After the war she opened our house for bed and breakfast, and then took on The Bay House and ran the café. In those days, it was very simple; there were coach parties, and campers arriving by bus or train for a fortnight’s holiday from Bristol, Swindon, Yeovil, or Crewkerne, and she did cream teas, crab sandwiches, egg and chips, that sort of thing. After that, she took on the Watch House café for several years, and of course I had to help, doing the spuds, and cleaning up. Then it was time for me to do my National Service, so I joined the Navy first as an ordinary seaman, then a midshipman, and finished up after two years as a sub-lieutenant. I had a marvellous time, saw lots of things abroad you wouldn’t come across in Bridport, but didn’t have to do anything very serious or warlike. And that reflected the time, the late 1950’s. Everything was gentle, the music was light-hearted and romantic; people wanted softness after the war, not the hard grunge and grime that came later.

Then my mother and sister took on the Riverside café. My sister had been in the Wrens, was good at accountancy. The café was a little old wooden building, very much egg and chips, beans on a good day, which they leased from the district council. It was very busy, and it was home from home for the fishermen who played dominoes endlessly, sometimes up to midnight in the winter months. It was more club than business. But my sister found another life and left the business, so that my mother found it hard to cope. I was helping out at the café, when I was asked to go on a sailing expedition with Eric Hamblett, who later became the Harbour Master.

There was a chap called Uwe Steffan, a Swedish/German, larger than life in every conceivable way, who arrived in West Bay with an old Swedish sailing ship called the Black Rose, and set about doing it up. He spread the word around the area that one day he would have his own ship and would be looking for a crew, which most of us treated with some scepticism having heard similar stories before. I’d got married in 1960, but it hadn’t worked out, so I was at a bit of a crossroads when I got a call from Uwe. He said that his ship, a three-masted schooner called Mary, was lying in Hamburg and he expected us there within the month. So off we went, Eric and I, and found the ship was a Baltic Trader, of over 100ft, with three timber masts 60-70 ft long. The plan was to sail to the Caribbean and fit it out as a sail training vessel for American university students. We sailed first to Portsmouth (collecting a stowaway en route) and then to Cherbourg to pick up ballast. Leaving Cherbourg that October, we hit a huge storm in the Bay of Biscay, and ended up at La Coruna with half the sails blown out. After we’d made repairs, we set out for the Canaries that November, but hit another, bigger storm off Cape Finistere, which we later learned was Force 12. We made it to the eye of the storm, but then the wind hit from the opposite direction and in the middle of the night we lost all three of our masts, leaving us drifting around for two days, cutting back the rigging. Fortunately the ship had an old engine, and we limped to Vigo in Spain. That adventure, during which I saw the biggest seas I’ll ever see in my life, cured me of ever wanting to go sailing again.

When I got back, my mother needed help at the café, so I slotted in quite nicely. That was 1963, and I thought it would do until I’d decided what to do next, and I’ve been here ever since. In the 60s and 70s we were regularly getting flooded, and the council would only renew the lease if we rebuilt at a higher level. To a design by architects Piers Gough and Roger Zogolovitch, the present restaurant was completed in 1976, and remains much the same today. West Bay was very traditional in the 60s and 70s, but then in the 80s, things began to change in West Dorset. There were second weekenders arriving, media people, lawyers and other professionals, who didn’t want chicken and chips; they quite liked the idea of fish, and fish on the bone, which we’d never contemplated. So we responded to what out customers wanted and developed ideas of our own, a sort of partnership really, but always trying to retain informality and contact with the locals.

I’ve never had much expertise with cooking; my role has only been to run things. Most of the creative skill came from my wife Janet; when she joined the business she introduced an entirely different expertise, and brought in great recipes. And we’ve always had fantastic staff, one of whom has been here for over 30 years, 3 of whom over 20 years. It’s not an exaggeration to say the place wouldn’t have happened without the brilliant staff, most of whom are local; some now have family members working here. We have never had the ambition or desire to enter the world of celebrity chefs or Michelin stars. We seem to have been important to the local community and to visitors, and that is how we hope to continue. Ive been involved for many years with local sports: playing rugby for Dorchester, water polo for Bridport, and as a founder of Bridport Leisure centre 35 years ago, of which I am chairman. West Dorset is a wonderful place to live!