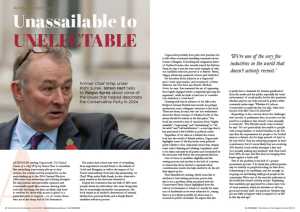

Former Chief Whip under Rishi Sunak, Simon Hart talks to Fergus Byrne about some of the issues that helped decimate the Conservative Party in 2024

Although reading Ungovernable: The Political Diaries of a Chief Whip by Simon Hart is somewhat like rewatching a motorway pile-up in slow motion, the content and his perspective on the years leading up to the 2024 General Election offer some very interesting and sobering thoughts. He may present uncomfortable opinions and occasionally speak like someone dancing while nobody’s watching, but they are likely only hard to swallow for those with an axe to grind or a particular party to support – or, of course, those who are at the sharp end of his frustration.

The author had a front seat view of everything, from negotiations around Brexit to the debacle of Covid and Partygate, as well as the impact of Liz Truss’s extraordinary forty-nine-day premiership. As Chief Whip under Rishi Sunak, he also observed a party unravel as the electorate deserted it.

Despite his contention that the bulk of MPs were ‘people driven by solid values’ who were ‘doing their best in increasingly intolerable circumstances’, the book stands as an insider’s observations of internal dysfunction, personal feuds, and a deeply flawed candidate selection process.

Ungovernable probably does pull a few punches but it still offers occasional shredding comments about former colleagues. Describing the resignation letter of Nadine Dorries, who recently joined the Reform Party, he says it was the very worst example of why our candidate selection process is so flawed. ‘Bitter, chippy, delusional, paranoid, vicious and vindictive.’

He describes Boris Johnson as a ‘hypnotist’ and a ‘total opportunist,’ and wonders if a Prime Minister can ever have any friends. Michael Gove, he says, ‘has mastered the art of appearing thoroughly engaged whilst completely ignoring the argument’, while he finds it hard not to consider Lee Anderson a ‘total knob.’

Chatting with him in advance of his talk at the Bridport Literary Festival next month, he perhaps understates some colleagues’ reactions to the book. There are those, he says, who are ‘not enthusiastic about the whole concept of whether books of this nature should be written in the first place.’ The book has received a mix of reactions, from “highly readable”, “engrossing” and “entertaining” to “tittle-tattle” and “self-justification”—a sure sign that it has punctured a few bubbles in political circles.

Regardless of its value as a behind-the-scenes look into the world of British politics, Ungovernable highlights some of the key issues every political party is likely to face. Important issues that, despite some critics claiming are whining complaints, need to be taken seriously by all parties and scrutinised by the electorate well before the next general election.

One of those is candidate eligibility and the vetting process, and another is the lack of a system to ensure that those elected to represent their constituencies receive the help needed to do the job they signed up for.

Peter Mandelson’s sacking, which some like to attribute to bad vetting processes, proves that this is not a problem solely associated with the Conservative Party. Simon highlighted how the Labour Government is ‘subject to exactly the same sort of headwinds as we were subjected to’, stating that it is not always possible, let alone easy, to succeed in politics nowadays. He argues that this is partly due to demands for ‘instant gratification’ from the media and the public, especially the ‘toxic environment’ of social media, but he also questions whether anyone can truly succeed in politics while constantly under siege. ‘Whether it’s Labour, Conservative or anybody else,’ he asks, ‘what does success look like? Can it be achieved?’

Expanding on his concern about the challenges new recruits to parliament face, he points out the need for a resilience that doesn’t come naturally to everyone. ‘The lifestyle needs some scrutiny,’ he says. ‘It’s not particularly favourable to people with young families, or indeed families at all.’ He says that the requirement for people to be ‘locked away in a distant city for large periods of time’ is all very well if they are achieving progress in their constituency, but it’s more likely they are receiving ‘200 abusive social media messages a day’ and ‘not actually making any headway’ with their brief. New MPs, he says, feel like they are banging their heads against a brick wall.

Part of the problem is the lack of a proper recruitment process. ‘I do think that political parties rely too heavily on people knocking on their door, volunteering to be candidates, and not enough on us going out and finding really good people in the community. We’re one of the very few industries in the world that doesn’t actively recruit.’ Explaining that candidates get appointed by a democratic vote of local members, which he describes as ‘all very good and worthy stuff’, he questions ‘whether that process fully recognises what is required of an MP in this day and age.’

Scale this situation up to ministerial level, and he goes back to the issue of vetting, suggesting that even if candidates for election pass a simple regional party vetting process, they are rarely assessed on whether they could make a good minister, whether that involves the ability to make crucial decisions on health or even determine a nuclear strategy in times of conflict. The one thing that is seldom evaluated is whether they have the skills to work at that level. ‘We might be able to decide whether this person would be a good MP, but would they be a good minister is a very different question.’ The transition from MP to minister, and what is required of a minister with a ‘huge budget, a massive team of civil servants, and multiple responsibilities’, is something that is not researched, he says. ‘We just chuck people into these roles. You might put somebody into the MOD who’s got absolutely no knowledge about procuring, for example, large weapons contracts. We kick them in there, with literally no training at all, and tell them, get on with it.’

It would be easy, and in some ways possibly true, to say that this is just making excuses for the apparent disintegration of a powerful political party—shutting the stable door after the horse has bolted. But having described the Whips’ Office as a field hospital, into which ‘damaged colleagues are delivered, patched up and returned to front-line duties,’ Simon views the process with a seasoned perspective that affects every party across the board. Time and again, he says people enter politics thinking they could ‘change the world’ or ‘broker world peace’ or pursue ‘some high-level dream,’ when the reality is quite different. Success in politics, he argues, is measured in tiny percentages. ‘You’re able to make a sort of 1% difference, or a 5% difference to the particular cause you’re wedded to—that’s success. That’s what success looks like.’ Many jump in ‘full of energy, full of zeal,’ but then the ‘life is sucked out of them within about five years, and they’re then very disillusioned.’ This disillusion, he says, makes them more susceptible to ‘sometimes acting in a way that is somewhat unattractive to the public.’

Despite declaring that most misdemeanours are the result of normal human frailties rather than ‘intentional malevolence’, Ungovernable details some of the Whip’s office ‘field hospital’ duties, which few would describe as ‘normal’ human frailties. The book details occasions such as extracting a colleague from a brothel at 2.45 in the morning, dealing with an employee dressed as Jimmy Saville having sex with a blow-up doll, as well as questionable financial dealings, explicit photos and inappropriate social media posts. Not to mention shocking displays of entitlement in bids for honours. As Chief Whip, Simon Hart oversaw a hub of crisis management, handling scandals and legislative compromises while maintaining party discipline and morale during turbulent times. All in a day’s work.

The end result, he says, is that ‘the overall appeal of politics as an honourable career’ has been eroded, and it is gradually wearing away. ‘And I think people look at it now and think, Oh, why would I want to do that?’

So, what are the skill sets that might help MPs survive the political cauldron? Having served with the Territorial Army for five years, he suggests that although it’s a very old-fashioned view, a services background could benefit those pursuing a career in politics, partly because military training can prepare individuals to handle unforeseen circumstances. ‘It maximises your physical and emotional resilience,’ he says, and prepares people to cope with ‘chaos and disappointment.’ When things don’t go as expected, ‘the correct reaction in those moments isn’t to fall over in a heap or just blame somebody else, it’s to pick yourself up and just get on with it, find another way and make the best of a difficult situation.’ You have to deal with challenges, he says. ‘Nobody owes you a living.’

Ungovernable, and some of Simon Hart’s insights don’t paint the country’s politics and governability in a flattering light. Pointing out that Labour’s victory was less about their policies and more about the electorate’s rejection of the Conservatives, Simon suggests that Sir Keir Starmer and all parties trying to win power share the same issues. ‘The problem for Starmer,’ he says, ‘is that Labour made the same mistake we all make, and I suspect Reform is making too. That is promising instant gratification in a way that cannot possibly be delivered.’

One of the reasons the ‘public is impatient for change’ he claims is because they have been promised ‘results and outcome’ by each party. And the reality is that ‘these things are complicated’. Stopping the boats requires a ‘multinational approach to a global problem’ which he says will take years to achieve. ‘The noise from social media is they’re just as useless as the people before, so we should ditch them as well. It’s impossible for Starmer.’

He describes Nigel Farage as ‘the sort of pub bore who stands at the bar shouting about foreigners,’ but points out that Reform is ‘a business of which Farage is the major shareholder, so there is a commercial incentive at play.’ He says Reform is playing the same game as other parties. ‘They’re concentrating on trying to win and making a lot of quite rash promises in the process.’ It’s a strategy from a well-worn playbook that we have seen in many countries around the world. ‘Members of Reform do sail remarkably close to the wind,’ he says, ‘and when it comes to stirring up fear and hatred, it’s a pyromaniac thing, really, isn’t it? You light the fire and then blame somebody else and say that only you can put it out. That worries me.’

Written in a diary-style format, Ungovernable offers candid observations and insights into the systemic issues, emotional toll, and public disillusionment that defined a turbulent era in British politics. Simon Hart, in conversation with Sir Oliver Letwin will no doubt be a fascinating extension of these insights.

Simon Hart will be in conversation with Oliver Letwin at the Electric Palace on Sunday 2nd November @ 2.00pm. For tickets visit: www.electricpalace.org.uk/

or telephone 01308 424901.

Ungovernable: The Political Diaries of a Chief Whip by Simon Hart is published by Pan Macmillan. ISBN number: 9781035068791