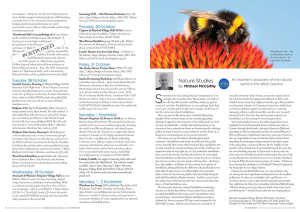

Sometimes we have likings that are instantaneous. For example, the comedian Eric Morecambe, one half of the old duo Morecambe and Wise, made me grin as soon as I saw him. He didn’t have to say anything. I just had to set eyes on him and I would start to laugh. And I sort of feel the same way about bumblebees.

How can you not like them, these colourful flying furry bundles? How can that shape not be instantly appealing? (Perhaps it appeals to the remnants of the child inside us.) And are they not admirable—visibly hard-working whenever we encounter them, going from flower to flower patiently collecting pollen, in sharp contrast to wasps which we tend to think of as dangerous unwanted guests at our summer picnics?

Of course, on one level that is all anthropomorphic nonsense—bumblebees and wasps are both just doing what comes naturally. But on the other hand, the likes and dislikes that we take towards the natural world are part of life, and I have the impression that most people are, as I am, instinctive bumblebee fans, even if they know very little about them. So, some quick facts: bumblebees are like honey bees in that they live in colonies, but whereas we have just one species of honey bee—the honey bee, Apis mellifera—in Britain we have twenty-four species of bumblebee, distinguished by the different coloured bands across their tails, though most of us will probably only encounter three or four of them in our gardens (the most likely being the buff-tailed bumblebee, Bombus terrestris.) And the reason I raise the subject here is that last month I was concerned to hear two pieces of bad bumblebee news.

The first came from the national bumblebee monitoring scheme run by the Bumblebee Conservation Trust, which revealed that 2024 was the worst year for bumblebees since records began. Across Great Britain, bumblebee numbers declined by almost a quarter (22.5 per cent) compared to the 2010-2023 average. And the second came in a new piece of research about the Asian hornet, an invasive species from the Far East which first appeared in Britain in 2016, and, which I wrote about here eighteen months ago. This predator can devastate colonies of European honey bees which have evolved no defences against it, and can have a seriously damaging effect on other insect life; and the new research showed for the first time that four common species of bumblebee are also among its most frequent prey.

Now increasingly known as the yellow-legged hornet, to highlight its most characteristic feature, this beastie came to Europe through global trade, arriving in France in 2004 and spreading to other continental countries. It reached Britain in 2016 and became established in Kent two years ago. However, the one hopeful bit of news is that the fight to keep it from spreading, by beekeepers and government scientists, seems to be succeeding—at least in Dorset. By the middle of last month, 112 nests had been found and destroyed this year, but the overwhelming majority of them were in Kent; only two nests were found in Dorset, both in Verwood in the east of the county. Despite the fact that two nests were found in Portland in August 2023, there has been no trace of it since. “I think we have managed to eradicate it on Portland,” Duncan Fergusson, the beekeeper in our village told me.

Fingers crossed. Bumblebees are not only attractive: they are among the most significant and important of all our plant pollinators. Yet they are so familiar and—up till now—so common, that it is easy to take them for granted, and assume they will always be there. Just remember what Joni Mitchell sang: “Don’t it always seem to go, that you don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone?” And she knew what she was singing about.