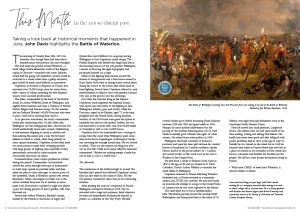

Taking a look back at historical moments that happened in June, John Davis highlights the Battle of Waterloo.

The morning of Sunday June 18th, 1815 was relatively clear though there had been heavy thunderstorms the previous day and overnight.

This had made the ground around Waterloo—a small village twelve kilometres south of the Belgian capital of Brussels—saturated with water. Infantry would find the going soft underfoot, cavalry would be restricted to a canter rather than a gallop and heavy guns would be much more difficult to manoeuvre.

Napoleon, re-instated as Emperor of France, had mustered over 70,000 troops since his return from exile—many of whom, including the elite Imperial Guard, were seasoned professionals.

The Allies, commanded by the head of the British Army, Sir Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, had slightly fewer numbers and were a coalition of British, Dutch, Belgian and German troops. To this number add on Gebhard Blucher’s 40,000 Prussians who were to play a vital role in securing final success.

As in previous encounters, the army’s commanders would play contrasting roles. On the Allied side, Wellington saw the battleground like a chessboard. He would methodically move units around, withdrawing at one moment, feigning an attack in another and then enticing the enemy into a trap. He favoured defence as much as attack, often using infantry in static square formations. Napoleon on the other hand was more prone to make bold, sweeping gestures with large groups of fighting men especially cavalry, spectacularly successful in some instances but occasionally disastrous on others.

Communications were a major problem in warfare during this period. Commanders on horseback viewed the action through telescope or dismounted to study maps spread on portable tables and then relied on riders to carry messages to various parts of the battlefield, which at Waterloo spread over several kilometres. Often, messengers lost their way as the action switched from one site to another or never made it all. Instructions sounded by bugle also played a part, but during periods of heavy gunfire, calls were drowned out.

Several days before Waterloo, Blucher’s troops, mauled by the French in skirmishes at Ligny and Quatre Bras, had withdrawn to re-group, leaving Wellington to face Napoleon’s initial charge. The French Emperor had delayed this lunge until late in the morning because of the soft ground. Wellington, a master at choosing the right topography, had positioned himself on a ridge.

Painted by Jan Willem Pieneman, 1824.

Much of the fighting then centred around the chateau at Hougoumont and a farm house named La Haye Sainte. Both were to change hands several times during the course of the action after much hand-to-hand fighting. Several times Napoleon refused to send reinforcements to help his most able general, Marshal Ney, and, in the process, lost the advantage.

Just when the outcome hung in the balance, Napoleon’s crack regiment, the Imperial Guard, were drawn into the centre of the fighting to face Wellington’s infantry, guns and cavalry, while the Prussians, urged on by Blucher, aged 72 at the time, ploughed into the French flank causing mayhem. Sections of the Old Guard were given the option to surrender but chose to die instead. Indeed, the cost had been heavy on both sides with over 40,000 killed or wounded as well as over 10,000 horses.

Napoleon had to be manhandled into a carriage to escape from the scene while Wellington spent some time on his horse Copenhagen, reviewing his troops and surveying the carnage around him. He was forced to admit, “That was the nearest run thing you ever saw in your life” while in his more reflective moments commented, “Believe me nothing except a battle lost can be half so sad as a battle won.”

The Aftermath:

The conclusion of the battle brought to an end ‘the hundred days’ period that followed Napoleon’s return from his first exile on the island of Elba. For the two primary combatants there were to be contrasting fortunes.

After heading the army of occupation in France, Wellington returned to Britain in 1818. He was rewarded with a large cash payment, feted wherever he went and immediately re-immersed himself in politics as a member of the Tory Party. He held several cabinet posts before becoming Prime Minister between 1828 and 1830 and again briefly in 1834. Perhaps his most notable achievement was the passing of the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829 which essentially gave Catholics the rights of other citizens. He retired from active politics in 1849.

Wellington then held a number of honorary positions and spent his time split between his country house in Hampshire, his London residence, Apsley House, known by the postal address of 1 London and several castles on the south coast in his role as Warden of the Cinque Ports.

He died from a stroke at Walmer Castle, Kent in 1852 at the age of 83 and was buried in St. Paul’s Cathedral. Today’s Arthur Wellsley is currently the ninth Duke of Wellington.

Napoleon returned to France following Waterloo, abdicated and, as France reverted to a monarchy under Louis XVIII, was arrested. He may have made an unsuccessful attempt to escape to the United States of America but he was soon captured by the British.

This time there was to be no Mediterranean idyll. The British put him aboard the warship HMS Bellerophon and transported him to the island of St. Helena, over eight thousand kilometres away in the windswept South Atlantic Ocean.

Here he moved into small premises, Longwood House. He seldom went out and spent much of his time reading, writing and talking with friends. His health had never been good and after falling ill with gastric problems died in 1821 at the age of only 51. Initially he was buried on the island but in 1840 his remains were taken to France where they now rest in a place of honour at Les Invalides in Paris which also houses a museum and facilities for disabled service people. He still has some distant descendants living in France.

- Word note (OED): to meet one’s Waterloo; A decisive defeat or failure.