Red, Roe, and Rogue. Dr Sam Rose looks at the complex impact of the UK’s deer species on natural recovery

In past episodes of the R-Word we have talked about the roles of cattle, pigs and ponies in rewilding. As major herbivores, they each play a role in causing Disturbance, in the Dispersal of seeds, and in the promotion of Diversity; the three Ds of rewilding. They work at different height levels in the ecosystem (I’m sure there is a technical word for that..?), with pigs foraging and rootling in the soil, cows grazing and doing low level browsing, and ponies grazing but significantly browsing higher up the shrubs and trees. But what about that other free roaming herbivore, the king of the mountains, the elusive Bambi, the unfortunate roadkill… what do the deer do?

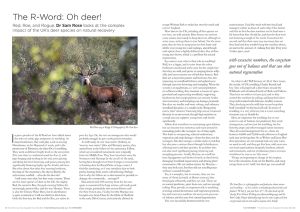

I will come onto that, but first some context. There are five main species of deer in the UK: the mighty Red, the secretive Roe, the pack-running Fallow, the increasingly present Sika, and the tiny Muntjac. There is also the Chinese Water Deer, but its distribution is quite restricted so I will not dwell on them here. Only the first two, the Red and the Roe, are native to post Ice Age UK, the rest are immigrants who would probably struggle to get a work permit nowadays.

As with many of our ‘non-native’ (Fallow), or ‘invasive non-native’ (Sika and Muntjac) species, they arrived here at the behest of the aristocracy. Fallow, which are considered naturalised, were originally from the Middle East. They have been here since the Normans took Hastings by the scruff of the neck, having been brought over from Europe as ornamental or hunting deer for Royal Parks or large estates. I find this confusing, as if you introduce deer to look pretty, hunting them seems self-defeating. Perhaps that is why the Fallow are as determined as possible to damage the countryside… revenge?!?

Sika arrived mid 19th century from the far east, again as ornamental for large estates, and made good their escape, particularly into eastern Dorset and the New Forest area. Finally, the little Muntjac was brought over from China by the Duke of Bedford in the early 20th Century and carelessly allowed to escape Woburn Park to make hay over the south and east of England.

Most deer in the UK, including all five species set out here, are wild animals. Deer fences are used on some estates, but mainly to keep deer out, although in some cases, to keep them in (see below). For the most part, they are free to jump your too-low fence and nibble your young trees and saplings, and although each species has a slightly different diet, they all love young tree shoots, which is a problem for natural regeneration.

So, context over, what is their role in rewilding? Well, it is a biggie, and it varies from the other herbivores mentioned at the start for the simple fact that they are wild, and prone to jumping fences willy-nilly (and not everyone can afford deer fences). Red deer act as keystone grazers and browsers, but also impacting on woodland habitats and upland areas through excessive browsing and trampling. When the system is in equilibrium, i.e. with natural predators or sufficient culling, they maintain a mosaic of open grassland and regenerating woodland, supporting biodiversity; but overpopulation can severely hinder forest recovery, and trampling can damage peatlands. Roe deer are smaller and more solitary, and influence woodland dynamics at a smaller scale. Being picky eaters, their ‘selective’ browsing helps create structural diversity in an ecosystem, though high numbers in a small area can suppress young trees and shrubs significantly.

Fallow deer contribute to maintaining open habitats but can become too numerous and roam around in marauding packs, like teenagers on a Friday night. This leads to overgrazing, reduced understorey vegetation and crop damage—from the deer, not the teenagers. Sika deer occupy a similar niche to red deer but also pose a serious threat through hybridisation, affecting native red deer genetics. In numbers they can also exert significant grazing, browsing and trampling pressure. Finally, Muntjac are small but have big appetites and browse heavily at shrub level, damaging woodland regeneration and altering plant communities. Do not underestimate the Muntjac—they may look cute, but they will eat your Begonias without a second thought.

Yes, it is complex, but in essence, there are too many of them (certainly in Dorset anyway), they breed quite efficiently, and they eat a lot. There are no natural predators, apart from cars, and not enough culling. They provide an important role in rewilding, restoring natural disturbance and vegetation patterns, but with excessive numbers, the ecosystem goes out of balance and that can slow natural regeneration.

This was beautifully demonstrated by two conversations I had this week with two local land managers within an hour of each other. One farmer said that in fact the deer numbers on his land were a bit lower than they should be, and that the deer were not browsing enough of his scrub. In contrast the second said that there were way too many deer on their land and they couldn’t keep the numbers down, no matter the amount of stalking they did. They were 5 miles apart, max!

So, what to do? Well because of all of these issues, the royalty of UK rewilding, Charlie Burrell and Issy Tree at Knepp built a deer fence around the Wildlands and introduced herds of Reds and Fallows. They have no wolves or Lynx (yet) and so they control the numbers by culling, and keep their farm shop well-stocked with delicious, healthy venison. They also keep out the wild deer so can keep their herd ‘unsullied’ by the local riff-raff. In terms of rewilding, it is very effective, but it is not something everyone can, or should do.

Deer are important for rewilding, but as our system is out of balance (no predators) they need management, and not just for rewilding, but for forestry, crops and other managed nature recovery. They also need management for us—there are between 40,000 and 70,000 road collisions in England each year involving deer. So as Wolves and Lynx (Roe deer specialists) are not coming back any time soon, we need to cull, and then get that lean, wild meat into our local supermarkets, hospitals, butchers, schools and restaurants, and not at ridiculous prices; venison should not be seen as an ‘elite meat’.

Things are beginning to change in this respect, but in the meantime, look out for Bambis, and enjoy seeing them in the ‘wild’, but don’t get too attached!