Nature’s ability to move people is something I have found more engrossing as I have got older. Of course, not everyone is moved by the natural world; I have friends who couldn’t care less about it. Yet I have other friends who are not only enthusiasts for landscapes and wildlife, but also have an instinctive emotional connection with the living world around us, which sometimes permits experiences which can only be described as profound.

A case in point concerns barn owls. Can an encounter with a barn owl be described as profound? Well, in my own case, yes—assuredly so. It is a bird which has a head start in charisma anyway because of the element of mystery carried by all owls as creatures of the night, which makes them prominent in folklore across the world; but what you get with a barn owl is something you don’t get with its fellow species like tawny owls: in the right circumstances, visibility.

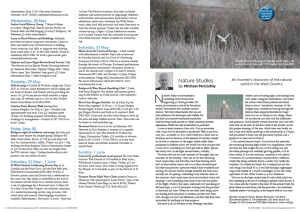

For barn owls are not only creatures of the night, they are creatures of the evening—they are, to use that charming word, crepuscular, and will often start their hunting about half an hour before sunset, and it is in these circumstances that they can provide a spectacle which I find wonderful and moving. It’s not just beauty, though beautiful the birds most certainly are. It’s perhaps something to do with the rarity of the occasion—how many times have you watched a barn owl hunting?—and something even more to do with the quality of the flight, which is this silent, unhurried, low quartering of the landscape, a sort of mesmeric cruising over the grassland as they hunt for voles. When we see other birds flying, most are dashing from one place to another, are they not? Barn owls, though, are slow and deliberate, and they take their time, untroubled by anything but their purpose.

But most if all, it’s the time of day. Evenings with their stillness and soft fading light, and hunting barn owls, make a magical combination—my friend the nature writer Brian Jackman described them to me as “mysterious creatures of the twilight zone, soundlessly floating through the dusk on their exquisite thistledown wings.” And so it was in March, in our village, where we are blessed, not only with the bullfinches and primroses I have already written about this year, but with barn owls on all sides. In the first week of the month, on the first proper evenings of the year, which were very lovely, we had a barn owl which turned up at the cricket pitch at 5.15pm, and proceeded to hunt over the grasslands beyond, and a group of us went out to watch it.

I was moved beyond words. It wasn’t just the spectacle, the entrancing floating flight which was magnificent, above all when the bird caught the rays of the setting sun and the white plumage was suddenly glowing golden, as if lit from within. It was the occasion, somehow, it was almost a visitation, by an extraordinary creature from a different world; like being suddenly shown a reality very unlike the everyday. I’ve racked my brains for a comparison and the only thing I can think of is, it was like hearing a nightingale sing in the middle of a wood at midnight. It was the visual equivalent of that. What I mean is, it was wondrous.

You can say, don’t get carried away, it’s only a bird, and it was. But something in the act of watching it opened a door for me. It was a door into the wonder at the heart of the natural world, the place where we came from, and the place that—we sometimes suddenly realise—we long for, at the deepest level of our souls.