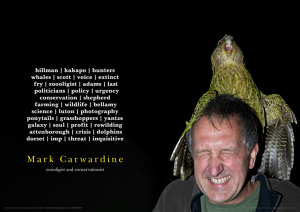

Mark Carwardine talks to Fergus Byrne about his life as a zoologist and conservationist and the growing threat that comes from within our own species.

Despite being shot at more times than he can remember, kidnapped by seal hunters, beaten up by chimpanzee traders, and molested on television by an amorous kakapo, Mark Carwardine believes that politicians are probably the greatest threat to the planet at present.

He argues that politicians, particularly in the UK, often lack a science background and fail to understand how essential conservation is to everything from farming and river management to economic development. ‘Politicians don’t have the knowledge,’ he tells me. He describes a ‘fundamental problem’ as the absence in Downing Street of anyone in the ‘inner circle’ of decision makers who has any knowledge or interest in the environment or conservation. ‘There is nobody there calling the shots for the environment!’ he says.

Speaking to me in advance of a talk at Symondsbury Estate in December, Mark says, ‘Politicians in most countries still see conservationists as weird and eccentric, you know, ponytails, white socks in sandals, hugging trees—an extreme interest’ rather than as an essential component of policy.

Anyone familiar with Mark Carwardine and his career in wildlife conservation, photography, and writing knows he presents a very different character altogether. In magazine articles, he has tackled stories such as the hypocrisy of greenwashing, the government’s laws against peaceful protest, and, most recently, rising hostility towards environmentalists.

Known as ‘the other guy’ because of the fame of those like Douglas Adams and Stephen Fry who have worked with him, he understands better than most the need for strong voices representing conservation. However, he is concerned about the fragmented nature of the conservation movement. He considers the conservation lobby a failure. Unlike powerful, unified lobby groups such as those for farming or fossil fuels, conservation involves ‘lots of different voices.’ He says there is an urgent need for conservation groups to come together—delivering ‘hard-hitting, simple points’ to cut through the noise of other influential interests.

He also emphasises the need for people, especially in government to understand the harsh reality of biodiversity loss in the UK. During his lifetime, the country has lost 70% of all wild animals. Like many of us, his childhood memories of grasshoppers, clouds of butterflies, and swifts filling the sky are now largely gone.

Born in Luton and raised in Basingstoke, he jokes that his seemingly unlikely starting point actually gave him the travel bug. However, he often claims that his extraordinary life has resulted just as much from luck as anything else. In a David Oakes podcast he recounts how, having recently finished his finals at university, he and some colleagues planned to meet in the insect house at London Zoo before going out to celebrate. He accidentally trod on someone’s foot, who turned out to be from the World Wildlife Fund and later offered him a job. Not long afterwards, he was asked to take some of the trustees back to the station after a meeting. Somehow, he managed to squeeze David Attenborough, David Bellamy, David Shepherd, and Peter Scott into a Hillman Imp, which promptly broke down. He credits the experience as a springboard to their being very supportive of his career, and he has never forgotten the memory of David Bellamy and David Shepherd pushing his car while David Attenborough and Peter Scott advised him on how to work his gears.

His career journey led him to Bristol, home of the BBC Natural History Unit, where he was based for 20 years before moving further south. When asked how he describes himself today, his answer is clear and immediate: zoologist and conservationist.

‘Conservation is what drives me,’ he says. ‘I’m a zoologist by training, and everything I do, whether it’s books or radio or writing or photography, is to do with wildlife.’ He sees his role as that of an interpreter—a vital bridge between the scientific community and those of us without the same degree of scientific knowledge, passing on crucial information about wildlife and conservation.

When I catch up with him at his home in Dorset, he is trying to get through a mound of admin. He has been travelling non-stop for five months and hopes to be home for what he laughingly says is ‘a record-breaking’ two months.

His prolific output—the books, the TV shows, and the continuous travel—makes me wonder what drives him. ‘I’m lucky in a way, because my passion is my work,’ he explains. When he has time off, he’s bird watching or doing something else connected to wildlife. However, he also admits to a fatal flaw that contributes to his relentless schedule. Laughing, he tells me that he’s a ‘very bad judge of how long things are going to take,’ and might even underestimate a project by years.

Mark’s upcoming talk focuses on the monumental project Last Chance to See. This endeavour began as a journey with his good friend, the author Douglas Adams of Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy fame. Beginning in 1985 they set out to track endangered species around the globe and meet the people striving to protect them. The result was an extraordinary book called Last Chance to See, where Adams, with his legendary wit and wisdom, described the journey and its many adventures.

Following Adams’ sudden death in 2001, Mark and Stephen Fry got together to produce a follow up. Twenty years after the original book, they embarked on a new, eight-month journey to see how the species and their guardians were faring, resulting in a book and a popular TV series.

Mark reflects on the remarkable similarity between Adams and Fry. Both were exceptionally tall, both had ‘brains the size of planets,’ and both possessed an unusual way of viewing the world that was invaluable to the project. As a zoologist, Mark would describe the aye-aye lemur they sought in Madagascar, for example, in scientific terms. Douglas Adams, he says, saw it as an animal with ‘a cat’s body, a tail like a squirrel on steroids, long thin middle finger like a twiglet, eyes like ET, ears like a bat and teeth like a rodent.’ In a talk Adams gave not long before his death, he added that it had “Marty Feldman’s eyes.” Stephen Fry added that it looked like ‘somebody’s tried to turn a cat into a bat.’

The main goal of the Last Chance to See project was to utilise Adams and Fry’s comedic talent and sense of adventure to attract an audience that wouldn’t normally read a book about conservation. They aimed to ‘creep up on people with lots of funny bits and adventure… and then hit them with the facts.’

Douglas Adams fans will recognise the last remark made by dolphins when they chose to leave the planet as it was being demolished to make way for a hyperspace bypass. “So long, and thanks for all the fish” they said. It became the title of the fourth book Adams wrote in the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy series. In Last Chance to See, Mark and Douglas Adams searched for the Yangtze river dolphin, which was believed to be near extinction at the time. By the time he and Stephen Fry embarked on the follow-up, the dolphin was already extinct.

Mark, who has spent thousands of hours with dolphins talks about their human-like traits. He finds them ‘inquisitive’ and ‘emotional’, with a tangible awareness that affects people in a deep, often emotional way. Dolphins, he says, are ‘good for the soul’.

I ask Mark whether he and Stephen Fry have discussed the idea of doing the project again. He points out that since the world is an even tougher place for wildlife now, there is definitely scope to revisit these issues, although the logistical challenges of coordinating their busy schedules would probably mean filming individual programmes rather than a continuous series.

In the meantime, many other issues occupy his time and passion. He discusses the debate between farming and rewilding, recognising the deep divisions. But he makes a clear distinction between industrial farming, which has the loudest voice, and many smaller-scale farmers who are not anti-wildlife and are actively rewilding parts of their land. He believes that non-intensive farming, working alongside nature, is entirely possible and beneficial, as a healthy ecosystem is vital for healthy farmland.

The ongoing controversy over badger culling, he says, is a clear example of the problem, where the industrial farming community, despite scientific evidence, continues to advocate for culling, confusing the public and other farmers. Mark believes that the root of such misguided efforts often stems from one thing: maximum short-term profit, not what is right for the environment and the long-term need for sustainability.

Ultimately, the systemic change Mark wants to see is for the government to fully incorporate environmental and conservation concerns into every decision it makes. He wants it to be part of energy policy, farming policy, and all government policies, not just a side issue.

He mentions how in the past, CEOs and managers of businesses have joined his whale watching trips, returned to their companies, and implemented changes to become more environmentally conscious. He considers whether a conservation-themed trip with top politicians, where they can witness the world’s wildlife firsthand, might foster a deeper understanding of the crisis and inspire them to return home with a fundamental shift in perspective.

As Mark Carwardine faces his mountain of post-travel emails and prepares for his brief respite at home, his work remains a potent, necessary call to action—a continuing mission to interpret the urgency of the wild world for a listening public and a sustainable future.

Mark Carwardine will be speaking at Symondsbury Estate on Saturday December 6th. Tickets are limited. To purchase one visit: https://symondsburyestateshop.co.uk/collections/all today.

For more about Mark visit www.markcarwardine.com.