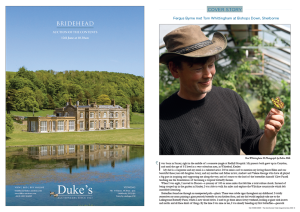

Fergus Byrne met Tom Whittingham at Bishops Down near Sherborne

‘I was born in Surrey, right in the middle of a concrete jungle at Redhill Hospital. My parents both grew up in Croydon, and until the age of 8 I lived in a very suburban area, in Whiteleaf, Kenley.

My dad is a carpenter and my mum is a talented artist. I’d be remiss not to mention my loving fiance Ellen and our beautiful three year old daughter Avery, and my mother and father in law, Andrew and Valerie George who have all played a big part in inspiring and supporting me along the way, and of course to the lord of the butterflies himself Clive Farrell teaching me the foundations of becoming a tropical butterfly farmer.

When I was eight, I moved to Dorset—a journey of 100 or more miles that felt like a total culture shock. Instead of being cooped up in the garden in Kenley, I was able to walk for miles and explore the Wiltshire countryside which felt incredibly liberating.

Butterflies found me through an unexpected path—plants. There were subtle signs throughout my childhood. I vividly remember my mum painting a giant peacock butterfly on our kitchen floor, and my dad would regularly take me to the Lullingstone Butterfly Farm, which is now closed down. I used to go there almost every weekend, looking at giant stick insects and moths and all these kinds of things. By the time I was nine or ten, I was already breeding my first butterflies—peacock caterpillars I’d found in hedgerows, raising them on nettles and then releasing them.

My teenage years were a blur of skateboarding and adventure. I was obsessed with skateboarding. I’ve also always enjoyed photography, and I used to do a lot of skateboard photography, filming and editing. Now I use photography more like a tool so I can remember when something is happening in conjunction with the point in the life cycle of the butterfly, or the type of growth the plant’s kicking out at certain times of year.

I’ve always had the mind of a collector and been fascinated by plants. Since the age of 18 I worked my way up through formal estate gardens, learning plantsmanship. I did a diploma at Kingston Maurward, but I’m essentially self-taught; I’ve just had very good teachers along the way, undoubtedly inspiring me and pushing me along. I became a self-employed gardener in my early 20s, working across Dorset and Wiltshire, subcontracting to various garden companies. As I learned more about plants, I started looking beyond manicured gardens to the wildflowers surrounding them.

At some point in my late twenties, my love for butterflies rekindled. I began breeding British native butterflies, which caught the attention of Clive Farrell, who noticed my skill set and invited me to become his butterfly breeder here at Ryewater. In 2022 at the age of 35 I had found my dream job I couldn’t refuse. What made this opportunity even more special was that my father-in-law, talented artist and habitat specialist Andrew George, was the designer of the 100 acres of meadows at Ryewater, which is now beautifully maintained by estate manager Wren Franklin—creating the ecological foundations where I now work. I also manage a six-acre meadow/butterfly reserve at Buckshaw House in Holwell, owned by Andrew and Sue May, where the habitat was also created by father in-law.

My current role is fascinating. I manage several glasshouses, producing tropical butterfly pupae that are sent to the Stratford Butterfly Farm. It’s a delicate process of creating the right environment for these incredible creatures. Butterflies, like many insects, over-produce—a survival strategy from being in the middle of the food chain. A single female butterfly can produce over 100 caterpillars.

Each day is different. It’s just such another world. It’s almost unbelievable that these things exist. But of course, they do. I grow hundreds of plants for feeding butterflies, and I’m constantly monitoring butterfly behaviour, watering plants, and managing the intricate ecosystems within the glasshouses.

It’s not just about breeding; it’s about understanding the complex relationships between plants and butterflies. Some species are incredibly selective about where they lay their eggs. The more I learned about butterflies, the harder it became to pull out weeds. If you’re a sympathetically minded person, you can look at your little patch of garden and think, I’ll leave that patch of nettles because a peacock butterfly might lay its eggs on it, or I might leave those docks because a small copper might utilize them. There’s this sort of balance between having a little bit messy, I call it shabby chic, and a little bit controlled. I think there’s a lot to be said for working at the pace of human nature rather than the pace of a machine.

The metamorphosis process still amazes me. Apparently, the genetic difference between a caterpillar and a butterfly is about the same difference between us and our earliest human ancestors. But there is a tiny strip of genetic code in that caterpillar. When they become a pupa, inside there is a liquid except for this little bit of genetic code, which then dictates what patterning to have, everything about it, and it slowly forms into that from a soup. It’s almost magical.

I’ve become particularly fascinated by tropical butterflies like the long-winged Heliconius, which have remarkable characteristics. They digest pollen alongside nectar, actually scooping pollen from specific jungle flowers such as Psiguria warscewiczii, and like a cow chewing the cud, they turn it into a protein-rich smoothie that helps repair their cells. I once had a butterfly I named Trevor that lived for 14 months—an extraordinary length of time for these creatures.

The butterflies we have here are jungle-dwelling butterflies; some species are completely happy in full shade.

The Heliconius, for instance, is a South American sub-canopy dwelling butterfly with a huge brain size compared to most butterflies. One of their common names is the postman because they can actually remember a route around the jungle, visually mapping out their environment.

The work is about more than breeding butterflies. It’s about education and conservation. We host various groups—botanical societies, schools, international visitors—to show them the intricate world of butterfly ecology. The decline in butterfly populations is scary, and not enough people understand the complex variables that support their survival.

Intensive farming and government policies have dramatically impacted butterfly habitats. By creating diverse, low-fertility meadows, we’ve seen incredible transformations.

At Buckshaw House, we’ve gone from having, say, 13 species present on the site to probably 33 seen annually, in just seven years. That’s directly linked to increased plant diversity, creation of complex land topography providing an increased amount of niches for many invertebrates.

My approach is about working with nature, not against it. You can’t control everything—sometimes you need to allow for things you might not want. It’s about creating a companionship between humans and plants, understanding that every element has its place in the ecosystem.

When a butterfly lands on someone, especially a child, it creates a memory that lasts a lifetime. That’s what keeps me passionate about this work—the ability to create those magical moments, to help people understand the incredible world of butterflies and plants, and to contribute to their conservation.

I feel incredibly lucky. Not many people can say they spend their days surrounded by hundreds of butterflies, understanding their intricate life cycles, and helping to preserve these beautiful creatures. From breeding my first peacock caterpillars to managing tropical butterfly breeding programs, it’s been an extraordinary journey. It might be the most unusual job in hundreds of miles, but I wouldn’t have it any other way.’