It’s a parade, a grand autumn parade of everything that the trees and shrubs have to offer in terms of their produce: hips, haws, sloes, crabapples, acorns, conkers, hazelnuts and berries of all kinds, and this year it’s visible like never before. So here’s a good look at it.

After Britain’s sunniest-ever spring and warmest-ever summer (and just the right amount of rain at summer’s end) 2025 has been the perfect year for the production of wild fruits and nuts in woods and hedges, as well as cultivated fruit in gardens, allotments and orchards. It’s what is known as a ‘mast year’, which happens only occasionally, when there is so much produce like beech mast that wild creatures cannot eat all of it, so some survives to produce the next generation of seedlings.

For that’s the point of all these berries and nuts: plant reproduction and spread. They’ve evolved to be attractive to birds and animals who will eat them and then, some distance away, poo out the seeds (or, like jays with acorns, bury them for winter consumption, then forget where.) We don’t really think of them like that, do we—as devices or instruments? For example, how would you define a fruit? A sweet and tasty version of a vegetable? Well, a good scientific definition would be: a seed dispersal mechanism.

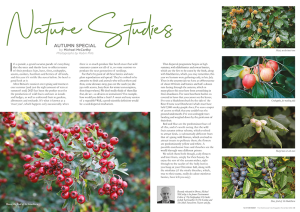

That dispersal programme begins in high summer, with elderberries and rowan berries, which are the first to be eaten by the birds, along with blackberries, which, you may remember, this year we humans were gathering early, in late July. Then in the countryside we have an efflorescence of about 40 fruits and berries and half a dozen nuts lasting through the autumn, which in many places this year have been astonishing in their abundance. I’ve seen hawthorn bushes so covered in haws that you cannot see the leaves; I’ve seen a blackthorn bush by the side of the River Frome near Dorchester which must have held 2,000 smoky-purple sloes; I’ve seen a carpet of acorns so thick that you couldn’t see the ground underneath; I’ve seen crabapple trees bending and weighed down by the profusion of their fruit.

Red and blue are the predominant hues of all this, and it’s worth noting that the wild fruit autumn colour scheme, which evolved to attract birds, is substantially different from that of spring wild flowers, which evolved to attract insects to pollinate them; the flowers are predominantly yellow and white. A possible conclusion: bees and thrushes see the world through very different prisms.

We relish them both though, early flowers and later fruits, simply for their beauty. So enjoy the rest of the autumn riches, right through to the scarlet of the holly berries you hang in your Christmas hall, along with the mistletoe (if the mistle thrushes, which, true to their name, really do adore mistletoe berries, have left you any.)