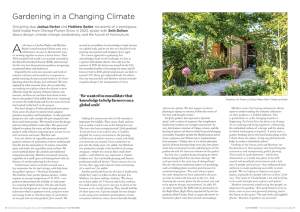

Designing duo Joshua Parker and Matthew Butler, recipients of a prestigious Gold medal from Chelsea Flower Show in 2025, spoke with Seth Dellow about design, climate change, biodiversity, and the future of horticulture.

At the heart of Joshua Parker and Matthew Butler’s award-winning Chelsea entry was a collaborative mission to demonstrate ways of working together to create a better future. Their 2025 coveted Gold medal is an accolade awarded by the Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) and reserved for the very best demonstration gardens, recognising exceptional talent and dedication.

Inspired by the innovative practices and work of scientists, farmers and researchers in response to global warming, the pair created Garden of the Future. Speaking about the design, Josh reflected: ‘We were inspired by what everyone does, the research they are working on in places where the climate is most affected; along the equator, Saharan climates, for instance, and how we can learn from them to have that in our gardens.’ Josh added that it was ‘surprising’ to receive the Gold medal and that the team involved had worked ‘really hard’ on the project.

The duo’s design at Chelsea prioritised innovations from across the planet to demonstrate adapted practices in gardens and horticulture. A solar powered pump was one such example the pair integrated into their small show garden. ‘We weaved it into the design and everything linked to each other. The green roof helped to capture the water and the solar powered pump is really efficient, irrigating up to an acre in size with no fumes and noise’, Matthew said.

Even the choice of vegetables grown reflected the garden’s embrace of polyculture, with its multifaceted benefits for the environment. ‘It creates a beautiful space and makes the vegetables more resilient. We used sacrificial plants like calendula and traditional companion planting’, Matthew continued, ‘growing vegetables in a small space and mixing them with cut flowers; it’s resilient planting for the future.’

Furthermore, current scientific research was a key inspiration for the duo’s design, with help from the garden’s sponsor—The Gates Foundation. The humble sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas)—which requires an average temperature of 21-26°C—was grown to demonstrate the viability of such crops in a warming English climate. The duo also learnt about the development of a bean through natural cultivation which is quicker to cook, using less water and energy to do so. ‘It’s these types of innovations we can put into our own gardens’, Josh mused. ‘We wanted to consolidate that knowledge to help farmers on a global scale, and to use this on a local level with growing sweet potato and chickpeas [Cicer spp.].’

It’s a novel approach to gardening that acknowledges head-on the challenges we face as a species with climate threats. Not only was the summer of 2025 the hottest on record for the UK, but unsettled weather is becoming the norm and it’s forecast that by 2030, global temperatures are likely to exceed 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. To address this, one measure Josh and Matthew actively consider in garden design is the incorporation of trees.

‘Adding the correct trees for its full maturity is important for wildlife. They create shade and you can sit under it and its not in the baking hot sun. The trees also have nesting material’, Josh pondered. ‘It doesn’t have to be a dense tree, it could be dappled. In a sunny environment, the planting and diversity of plants increases; sunny and shady environments are created. Ferns could then be put into the shady areas’, he added. For Matthew, one particular example is the hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna)—which was used in their small show garden—and which he says represents a ‘climate resilient tree’ that can handle pruning and flowers producing small red berries. ‘Native insects also use it to lay their eggs and it doesn’t look overbearing; it’s a small tree’, he added.

Another profound focus for the duo is biodiversity which they strive to reflect in their designs. For Matthew, it’s about striking a balance: ‘We always try to have spikes of Verbascum and Salvia caradonna for small insects, but you’ve also got to factor in the humans so it’s visually pleasing. They should feel like it’s their space too. A good example for our designs is also using nine-centimetre potted plants or bare root plants which are more environmentally friendly and use less plastic. We also suggest to clients planting in spring or autumn, before the worst of the heat and drought comes.’

For Josh, gardens also represent a ‘dynamic space’, with a variety of purposes that complement biodiversity. Gardens are ‘complex ecosystems’, he says, that feature a mixture of foliage, texture, and the layering of plants and flowers reflect long and changing seasonality. Examples include the Mediterranean native Cistus x purpureus and African native Sorghum bicolour. Josh continues: ‘I think a lot of it is about education and it’s all about learning things every day; how plants work, how environments work, and what areas of the gardens do well. It’s about an evolution of the garden.’

So, how else is garden design changing to reflect climate change? Josh has one clear message: ‘We can’t get stuck in the same way of doing things’. He cites the more traditional aspects of gardening, such as bedding plants raised in greenhouses for commercial purposes. ‘You can’t always expect the same thing that we have expected in the past; we have to work with how wet or dry it is. And choosing the correct plants for the correct soil, and to be open to change and evolution’, he adds. It’s an ethos shared by the RHS with its promotion of the Right Plant, Right Place popularised by the late gardener, Beth Chatto. Such an approach strives to harmonise plants with their natural surroundings.

Matthew states that having enthusiastic clients open to understanding the climatic influences on their gardens is a helpful addition. This is particularly so as the changing weather is happening ‘far faster than the plants can change; it’s an evolving and living organism’, influencing the embodied carbon of a design and the degree to which landscaping is required. ‘I rarely leave a garden thinking about the hard landscaping, rather I think about the plants. Using recycled materials helps to reduce embodied carbon.’

Looking to the future, Josh and Matthew see the direction of their practice also benefitting the community and incorporating public planting. Their work in south Somerset—which they characterise as ‘a really nice place to be with coastal and woodland environments and a real mix of people and artisans’—has influenced their ambition to make gardening accessible to more people. ‘We are hoping to improve our green spaces, especially for people who live in flats’, Josh says. ‘The town of Chard floods a lot and we’d like to do work through water capture with plants.’

Matthew concurred, emphasising that people are important for gardens. ‘You need humans to be in there, even as your own personal planting; you’re the factor in that space.’ He ends with a thoughtful phrase: ‘Humans in gardens are essential.’