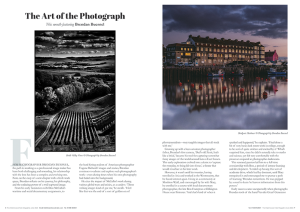

For photographer Brendan Buesnel, the path to working as a professional image maker has been both challenging and rewarding, his relationship with the lens has been a complex and evolving one. Now, on the cusp of a new chapter with a fresh work space, Brendan reflects on his journey, his philosophy, and the enduring power of a well-captured image.

From his early fascination with Don McCullin’s wartime and social documentary assignments, to the hard hitting realism of American photographer Eugene Richards’ images and stories, Brendan continues to admire and explore such photographer’s work—even during times when his own photography had faded into the background,

He cites the impact of McCullin’s work during various global wars and crises, as a catalyst. ‘Those striking images kind of got me,’ he recalls. ‘I feel like that was the end of a sort of golden era of photojournalism—very tangible images that all stuck with me.’

Growing up with a keen amateur photographer father, Brendan’s first camera, ‘Dad’s old Zenit, built like a brick,’ became his tool for capturing somewhat fuzzy images of the world around him in East Sussex. This early exploration evolved into a desire to ‘capture the everyday, to bring life into focus,’ a theme that would resurface in his later work.

However, it wasn’t until his twenties, having travelled in Asia and worked in the Westcountry, that he found interest again. Living in a community at Monkton Wyld, and encouraged by his wife Mary, he enrolled in a course with local documentary photographer, the late Ron Frampton at Dillington House near Ilminster. ‘And that’s kind of when it sparked and happened,’ he explains. ‘I had done a bit of very basic dark room work in college, enough to be sort of quite smitten and excited by it.’ Which surprised him, since he didn’t naturally take to maths and science, yet felt very comfortable with the processes required in photographic darkrooms.

This renewed passion led him to a full-time associateship with Ron, a period of intense learning and development. ‘I ended up having this sort of academic drive, which had lay dormant, until Mary recognised it and encouraged me to pursue a path of learning,’ Brendan remembers. He was gripped by a need to learn ‘to harvest information from this person.’

Early success came unexpectedly when photographs Brendan took of the band Van der Graaf Generator ended up on their album cover and in Mojo magazine. ‘I just happened to be around, in North Cornwall, when they were recording a new album and took some photographs,’ he explains. ‘Then one day a cheque just drops through the door with a note saying, “thanks a lot”. It was brilliant.’ This pivotal moment provided the ‘spark, the inspiration to carry on as a professional photographer, rather than a student.’

However, navigating the world of professional photography was not without its challenges. Brendan found himself taking on a variety of jobs, from weddings to commercial shoots, sometimes struggling with the constraints of art direction and the pressure to constantly seek work. ‘I very quickly got disheartened by the whole industry,’ he admits. ‘I realised that I couldn’t afford to say no to any work, and so much of the work I was doing just wasn’t where my passion lied.’

In the meantime, Brendan spent time cooking for River Cottage in Axminster and took on the job of doing the photographs for the Tim Maddams River Cottage Game Book. He also became involved in the arts sector in the Southwest, working with organisations like Walk the Plank and B-side. This period allowed him to hone his skills and explore different facets of photography.

Today, he is embracing a new chapter, setting up a new dedicated space. While the new studio marks a fresh start, Brendan’s core philosophy remains rooted in the power of photography to connect with the human experience. ‘At the risk of sounding too cliched, I think a big part of my photography is about preserving today for tomorrow,’ he reflects. ‘I think of my grandkids coming across my photographs and seeing this visual kind of portal into the past.’

Looking ahead, he is excited about the possibilities the new workspace offers. With commissions coming in from far and wide, Brendan looks forward to a diverse and visually stimulating workload.

Alongside his comissioned photography, Brendan is driven by social commentary, especially social injustice. He wants to create images that evoke empathy and inspire positive change. ‘Anything that sparks compassion in people, or that triggers a want for a better world or makes someone maybe think twice about an action or an opinion,’ he explains. ‘If I could produce one photograph that makes one person reconsider their approach to the world for the better, then that’s great.’

While acknowledging the challenges of pursuing such work without commission, Brendan is considering projects with the aim of a future exhibition and publication, a way of taking control of his artistic direction.

Brendan’s journey has been marked by both challenges and triumphs. His passion for photography, initially sparked by powerful images of human experience, has endured through periods of dormancy and professional hurdles. Now, with a new space and a renewed sense of purpose, he is perhaps poised to step into a brighter future, looking forward to capturing the world with a unique and compassionate eye.