The idea that we can somehow turn the clocks back and create peace between the western coalition that went to war in Afghanistan and Iraq, and the people whose lives were decimated by those decisions, does seem somehow ludicrous. The collateral of sympathy for the west, banked by the horrors of 9/11, has long since been cashed in and the increasing death toll of innocent people has helped to create a growing army of people determined to take life for life. Over the years, efforts to stamp out those that perpetrated the horrors at the World Trade Center and bring terrorists to justice have meant that many innocent people have been imprisoned as well as killed.

In a new book, Dorset based lawyer Clive Stafford Smith paints a bleak picture of how justice has been handled under the guise of western democracy. He offers an insight into some of the abuses suffered by prisoners in Guantanamo Bay as well as the many other prisons used by coalition forces. However, he also offers a message of hope for the future.

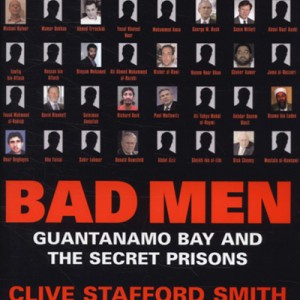

In the book, Bad Men: Guantánamo Bay and the Secret Prisons he recounts some of the details given by his clients about their treatment, both during the time prior to being flown to Cuba, as well as after their arrival there. It is a horrifying tale of first-hand accounts from one of the few individuals who has had independent access to the prisoners. However, Clive explained that much of what he has learned is classified. “I have to sign an agreement that everything my clients tell me is classified and I have to get the permission of the American military to write about it” he said. “And I really can’t talk about those things that they don’t want me to.” However, he did find a way to bring some of his knowledge to light. He explained how his efforts with a British client, Mozzam Begg who was later released, paved the way for change. “It was a big battle. In Mozzam’s case, they classified every word about how he had been tortured – and their rationale was bizarre. They said, these are the methods of interrogation that we use and therefore you can’t reveal them because they are classified. And what I had to do with that was absurd. I ended up sitting in their little secure facility writing a letter to Tony Blair – the theory being that I would write it to Tony and I would challenge them to censor it. And of course, they did censor it all. But you were then allowed to reveal this to the world, which was so embarrassing that they had to change the rules, and now they will let out evidence of abuse of prisoners – for the most part.”

Horrifying as torture may be, there will be many who believe it to be a necessary tool in the fight against global terrorism. Clive admits in his book, that in 2002 he could never have believed the US government could be in the business of torture. Remembering his naivety he says “You have rogue people in America, there are sheriffs who have done some pretty bad things in my time but I would never have thought that, as a systematic policy, the American government was engaging in torture.” In 2004 he was asked by Channel 4 to present a documentary with the somewhat bizarre title Is Torture a Good Idea? It gave him an opportunity to meet and try to understand some of those that saw value in it. He interviewed academics such as Professors Michael Levin and Alan Dershowitz as well as Bush administration heavyweights including Richard Perle. Whilst the ticking-time-bomb-scenario, where the need to extract information to save lives in imminent danger, could be forcefully argued, the need to use torture for other reasons seemed far more flimsy. And when many of those that suffer are likely to be innocent, it seems morality has taken a back seat.

Explaining that the military system of justice is not exactly open to scrutiny, he said, “In Guantanamo, there is a closed system, a secret system where there is no review at all. When I first went down there I thought I was going to have some difficult explaining to do as to why they [his clients] had been in Afghanistan. We’ve done a study now based on the Federal Government’s own figures and 95% of the prisoners there were not captured by the Americans at all – contrary to what Donald Rumsfeld said. And seriously, I had a hard time coming across anybody who was a terrorist. It’s hard to say how many had been bought by bounty but fortunately, President Musharraf published his autobiography and boasted about how many people Pakistanis sold for bounties, and it correlates fairly well. Out of my clients, I couldn’t put a figure on it, but I would say that a majority were sold.” According to Musharraf’s memoirs, the bounty figure was millions of dollars.

Clive was honoured with an OBE for ‘humanitarian services in the legal field’ in 2002. For over 25 years he has represented inmates on death row in America, many of whom have been proven innocent, and today he works as Legal Director of the charity Reprieve which he founded in 1999. It represents prisoners facing execution at the hands of the state in the conventional criminal justice system. Since taking on the might of the American military justice system, by representing ‘enemy combatants’ incarcerated at Guantanamo Bay in Cuba, he has returned to the UK and his book was published in June.

His introduction to law came in a very roundabout way. After growing up in England, the son of a Newmarket Stud owner, he travelled to America to study journalism after the family business ran into difficulties. As part of his University course, he visited death row inmate Jack Potts in Georgia to write a profile on him. “I first went there for a summer because my programme at University paid me to do that,” he said. “I met this guy Jack who was constantly dropping his appeals and trying to get executed, so I became friends with him. He ended up being on death row for 34 years and eventually died of old age in December 2005. It was during that time I realised that these guys needed lawyers more than they needed journalists”.

He was shocked to find that people on death row weren’t allowed legal aid after their appeal has been denied – a law that also applies to those serving life. Although this lack of rights may seem shocking to many, there are those that will argue that guilty people don’t deserve much sympathy. The question is, however, how many really are guilty? Stafford Smith says that guilty or innocent everyone deserves a defence. He says “Most of the people you represent are not innocent but there’s a fairly shocking number who are. I’ve never had a guilty person get acquitted in a death penalty case but the issue is preventing them getting executed. So that’s easy for me, it’s black and white. I don’t care who you are, you shouldn’t get the death penalty. I think everyone deserves a defence. The American judicial system is in many ways a good system but it just does the most bizarre things. The number of innocent people that I have ended up representing is quite scary.”

Clive maintains that unjust practices are not the way forward if we are to untangle ourselves from the web of violence that governments have helped to spin. It is clear that the world is an infinitely more dangerous place since the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and the many thousands of prisoners held in Guantanamo Bay and other secret prisons are simply potential new recruits for the future. The correlation between the propaganda power of the Maze prison in Belfast in the 70s and its effect on IRA recruitment, and the effect the current prisons have on al-Qaeda terrorist recruitment is a lesson we should by now have learned. In his book, Clive cites ways in which we can try to come back from the madness that is fuelling the violence. These may revolve around the clichéd terms of common decency and honest standards but they are the very cornerstones of social stability that can also help beat those that are beyond reason. There are many more people in the world that want peace than don’t; there is surely no sense in empowering those that thrive on conflict.