While many people reevaluated their work-life balance in the aftermath of Covid-19, it was also a time when people looked for new hobbies or took existing interests to another level. Olympic diver Tom Daley, for instance, became obsessed with knitting, actress Florence Pugh expanded her cooking skills, and David Beckham took up beekeeping. While closer to home, film location scout and manager Eddy Pearce developed a newfound passion for something he had been doing for years—photography.

As a location scout, part of his job is to find locations that match a film director’s vision. To do this, he not only has to find locations and view them through the eyes of those he’s working for, but he also has to photograph them in a way that sparks the imagination of those choosing where to film their latest project. It’s an art form that not only keeps him in demand but, over many years, has given him a platform to develop his own photographic vision.

His journey into photography is unique, and as he points out, ‘didn’t start when someone gave me a camera as a present’. That said, he chuckles at the memory of first using his dad’s camera on a family holiday. He enjoyed capturing moments with his family, but on the way back to the car after returning home, he remembers bending down to tie his shoelace. He put the camera down and promptly forgot it. The camera was lost, along with the photographic memories of the holiday.

After studying African and Middle Eastern Geography at university and taking photographs for the student newspaper—‘without any clue as to what I was doing’—he got a job as a runner in a film studio. He never looked back. And his distinctive journey was shaped by a piece of strategic advice. A friend in the industry told him: ‘If you’re going to shoot your location, shoot it well, because taking good photos is a really powerful way to help sell the location.’ This practical experience taught him to think ‘cinematically,’ developing an eye for composition, symmetry, and ‘dirty frame’ techniques like shooting through foreground objects. This would later influence his personal work.

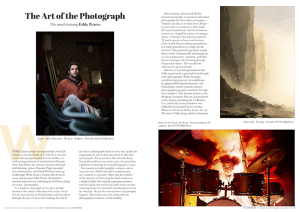

However, it was during lockdown that Eddy experienced a personal breakthrough in his photography. While shopping and delivering groceries for neighbours, he glimpsed life behind doorways and behind glass, which inspired a project photographing people sometimes through their windows. This became known as the Bridport Lockdown Project and produced iconic images, including one of Reuben Coe, whose life during lockdown was brilliantly documented by his brother Mannie in the book brother. do. you. love. me. This led to Eddy being asked to document a local vaccination centre—a very real-world setting where he felt compelled to capture what was happening. ‘I realised how much I enjoy doing community projects,’ says Eddy.

This shift culminated in the ‘Bank of Dreams and Nightmares’ project. Inspired by a late-90s project run by a photographer in Hackney Wick, Eddy, along with two other photographers Pete Millson and Dot Forrester, ran workshops for children in a local school. They gave the children point-and-shoot cameras to document their lives for a month. The outcome was deeply satisfying, offering immediate, genuine feedback that contrasted with the often slow-moving commercial world. He experienced profound enjoyment in doing ‘something that’s not about you.’ For the children, the project was empowering, giving them a voice and an ability to share their unique reality.

These projects and their move to portraiture, though initially uneasy, grew into a genuine desire to connect. He realised the camera was more than just a tool for capturing a place; it became a means to foster empathy. ‘It helped give you an appreciation of other people’s lives and how different they are.’ When people ask him about the most remarkable location he’s ever visited, he says, ‘It wasn’t the location, it was the people, or the experience you have when you are there.’

He also found a sense of discovery in the creative process. ‘I got so much pleasure out of going somewhere really dull and coming away with great shots,’ he says. ‘It makes you realise that the place wasn’t dull at all.’

He vividly recalls an early experience in a university darkroom, losing himself completely in the printing process, only to emerge for a lunch break hours later to find it already evening. This ‘flow state’ is something he still seeks: ‘Sometimes you will just get in that zone where you’re completely lost in it… It’s a really nice thing.’

Photography also has the power to evoke moving effects. One series of photographs he created to explore a traumatic event shows items recovered after a house fire. Three weeks after moving to Dorset with his wife and two daughters, he went to work on a job in London, only to get an urgent phone call from his wife telling him she was sitting in a fire engine watching their house burn down. A chimney fire had ravaged the entire building, and they lost everything. Later, he collected the charred remains of items he managed to recover and, after many years, photographed them. He recalls seeing them as ‘weird’ and yet ‘curious’. They were ‘personal possessions that had melted’. The result is a poignant and somewhat eerie collection of half-burnt children’s toys, books, bathroom paraphernalia, and even a camera.

It was the first time he had approached still-life photography, treating it as an ‘experiment.’ By taking on this creative challenge and transforming painful memories into art, he found a necessary distance and philosophical acceptance: ‘If it’s gone, it’s gone.’ Later, a subsequent meltdown and a panic attack revealed the mental toll of the event.

After learning more about the effects of such a traumatic experience, the integration of his craft with mental health awareness is now central to his work, notably through workshops with the local support group, The Harmony Centre in Bridport. Initially, he aimed to teach mindful walking, but the focus quickly became about human interaction and empowerment. The project with Harmony explored how photography might be used mindfully or to develop connection and community. His work with volunteers and visitors will be explored in a future issue of The Marshwood Vale Magazine.

Looking back on his career to date Eddy says he would ‘really struggle to name any individual influences.’ He is constantly looking out for new ideas and techniques. ‘I think that a lot of my influences in that sense come from cinematographers rather than other photographers. Hence the 16×9 format that I use for a lot of my photos—even for some portraits—which is pretty non-standard and definitely owes more to films than photos.’

To learn more about Eddy Pearce and his photography visit: https://www.eddypearce.com.