I was born in April 1957 here on the farm, at Fairmile, beside the Old Sherborne Road. My father was drilling grass seed that day in a nearby field, in those days of course his presence only being required at the conception of his children. Dad, like me, was always a working farmer; he drove with the men, and there was a team of men working here then – Roy Dunford, Ralph Brown, Bert Yarde, Albert Fuller; and Arthur, who was so driven by economy that if he knew he was working with someone else the next day, he wouldn’t wind his pocket watch so it didn’t wear out so quick. Then as well as my mum and dad there was Uncle Jack, Uncle Farmer, and Auntie Girlie. There were cattle here then, about 70-80 beef animals, and before that there was a dairy which was sold in about 1955. During and after the war, like everybody else, they were encouraged to clear land to grow more crops, so a lot of that went on, which is why we now have big fields. My family’s been here since 1910, so my Dad was also born here at Forston. When he married, my mother was living in a cottage at Fairmile, the other side of the farm, almost the girl next door. None of the rest of Dad’s family, Uncles Jack and Farmer, or Auntie Girlie, married, so my brother and I were fortunate to have the farm passed to us when we were of age. So today we own 1111 acres, of which we crop 1066, both conveniently memorable numbers.

I grew up on the farm, and went to Charminster School at age 5. I hated school pretty much all the way through. Typically it was off with the uniform, overalls on, and “where’s Dad working?”, when I got home after school. Miss Diment taught me to read and write, which I thought was strange because she had also taught my mum to read and write, and how on earth could anyone be that old. Then I went to Dorchester Modern School, and later transferred to Hardye’s to do A levels, because by then the penny had dropped that I needed A levels to get into farming college. Armed with one A level I was able to get a place at Harper Adams college in Shropshire, as were my brother Alan and sister Lizzie in due course. I did an HND Agriculture there, and looking back they were 3 of the best years of my life, making friendships there that continue today. 6 of us still meet once a year, and have done every year since 1978. College gives you a good understanding of all aspects of farming, which helps you ask the right questions as things change over the years.

The farm had been kept going while we were at college, and when Alan, Lizzie and I took over, the introduction of new blood was quite a game-changer. Lizzie then married another farmer, Bernard Cox, and in later years Alan retired from farming, so for the last few years it’s been just Mum and I running it. Mum’s now in a care home, so I’m fortunate to have a very astute right-hand man, Rob Greatorex, but when I talk about the farm it’s always “we” because it’s very much a team effort, with my wife Sarah supporting me in every possible way, as well as the various technical and professional advisors we all rely on. Sarah’s had her own career as an educational psychologist.

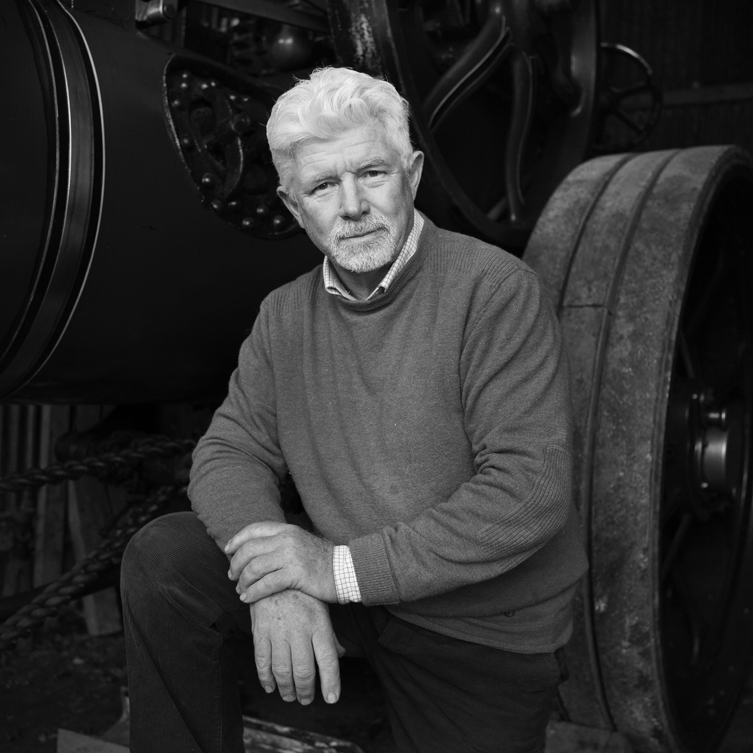

I wasn’t allowed to go steaming until I was an old git of 40. I’d had a Mamod steam engine as many boys did, so I was hooked from an early age. Then from the age of about 11 we had motorbikes on the farm; BSA Bantams, Greeves, a BSA C15, a Mako, all an absolute riot, but we were never allowed one on the road. That seemed such a shame, and if you enjoy a motorbike it never leaves you, but it never happened. So I bought Gladstone, a 1910 Clayton and Shuttleworth traction engine, when I was 39 and 11 months. The first year was a learning process, but I wanted to experience refurbishing a steam engine, so on advice from the boiler inspector we installed a new set of tubes, which gave us another 10 years of steaming. By then it was time for more refurbishing, which turned out to be a new firebox, boiler barrel, back head, smoke box, chimney base, and hind axle, all of which took 2 years pull apart, have components manufactured, and reassemble. That was some of the hardest work I’ve ever done, but like a lot of things, if you knew what it was going to be like in advance, you wouldn’t do it. And in the process, I’ve met some of the most interesting people on the planet, taken Gladstone to many shows and fairs, including the Great Dorset Steam Fair several times, and to Ireland twice. The Irish boys sometimes come over here; their names all end in “ie”, so there’s Jimmie, Billie, Willie, etc, and in the pub with them it’s impossible to buy them a beer because just as you go to buy a round, another one’s thrust in your hand. These days I try not to leave the county, so lately we’ve been to Shillingstone, and steamed to West Bay via the Hardy Monument. We’ve also got a 1901 Marshall portable, a sawbench, a stone crusher, and a thrashing machine, and it’s all great fun, even, or especially, when things go wrong.

Sarah and I met in ’83; she was doing a shift at the Royal Oak, Cerne Abbas when I popped in for a beer, and it went from there. She was studying for her second degree at Swansea. I visited her many times there on the Gower, which I thought was absolutely lovely, even more so because she was there, and we married in ’86. One of the few regrets in my life is not having built a big enough shed in which to store all the cars and motorbikes I’ve had and finished with. In it there would be the BSA C15, a 250cc Mako, a 3-litre Capri, a 2-litre Opel Manta in drug-dealer gold, and many others. But now I’ve got other cars, and all the steam stuff, and Sarah has her horses; she doesn’t know how much a ton of coal costs, and I’ve no idea what it costs to put 4 shoes on a horse, and we keep it that way.

We used to go windsurfing when we were fitter, which fitted quite well with farming. We could be on Overcome Corner rigging up on the beach 25 minutes after leaving the farm. It’s all much harder work now with traffic, parking, permits, etc. I tried kite surfing once, but thought I was going to die. It’s really hairy when it goes wrong, and I’ve been pulled under the water, then out again only just long enough cough up all the water I’d just swallowed before being pulled under again. I’ve seen people quite badly hurt, having been hoisted into the harbour wall or dumped in amongst the expensive properties on the seafront at Sandbanks. But the windsurfing was really fun. It had to be fast; you felt so alive, because of having successfully pitted your skills against wind, wave, and water, and it’s a good feeling to come home safe after a slightly risky pastime.

The joy in farming for me is seeing new crops emerge, with the sun behind them, no slugs eating the new rows, and all the tramlines in the right place, while you’re sat at the top of the hill in the tractor halfway through a Cadbury’s Creme Egg and a cup of coffee. But there are less people on farm today, so I talk too much because a lot of the time there’s no one to talk to. We’ve just bought a couple more fields and a wood, and nobody knows the name of one of the fields. I think it’s a niceness that all fields have names, many from hundreds of years ago. But the key to staying upbeat and fresh is to try to keep the hobbies up, and in that respect I’ve been fortunate. And to live and farm here in South Dorset is a privilege too. Sarah and I were lucky enough to go to Antigua for a holiday; many people said to me it must have been a version of paradise, and I thought it was all right, but it wasn’t Dorset.