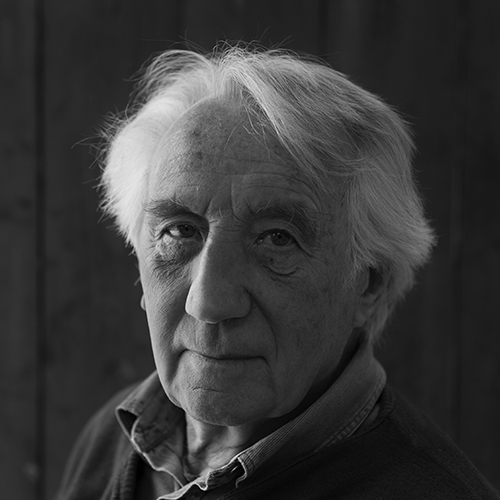

‘I was born in Yeovil maternity hospital in 1936. My mother died a couple of weeks later from septicaemia and complications following the birth; there were no antibiotics in those days. My father arranged for my paternal grandparents to bring me up, in Tintinhull, until I was 11, when my grandmother died. So basically I was brought up by Victorians. It was strict, but I was well looked after, and after passing the 11-plus at Tintinhull village school I went to Yeovil Grammar. My father was in the RAF in India, remarried during the war, and lived with his new wife and her daughter in a prefab in Montacute. So I went to live with them, where two more children were born, moving into a council house as the family expanded.

After the war, my father bought a milk round from a local farmer, supplying the villages of Montacute and Stoke-under-Ham. One day, someone from the village, who had an off-licence, suggested that we swap houses. So we moved from our council house to a lovely mediaeval hamstone house at the other end of the village, called the Shoemakers Arms. Officially it was an off-licence, but the regulars would lift up the counter shelf and come and sit in our sitting room. My father built up the business into a well-stocked shop, as well as continuing the milk round, and that really was my life until I left home.

At grammar school the one thing I really enjoyed was art, and I wanted to pursue that in life. My mother’s sister who kept a pub in Lyme Regis had always taken an interest in me, and I used to spend my summer holidays with her, which was brilliant. She suggested I could be an architect, and that sounded appealing, so she took me to Yeovil School of Art, where they designed a course which would get me in to architectural school. But in the second year I changed over to a Foundation course and then illustration, and textiles for my last two years. These turned out to be important choices, because I was introduced to printmaking, and learned lino block cutting, lithography, and printing on fabric, and after four years I had my degree.

From the age of 17 I had a parallel career as a racing cyclist. I was quite successful at a local level, three times champion of Yeovil Cycling Club. Due for my National Service, I was approached by the head of the Army Cycling Union. He said that if I joined the army, I’d be sent to Aldershot under his command, and he could promise me all the cycling I could handle. So I spent a very enjoyable two years’ National Service either cycling for the army, or doing a course called “tactical sketcher” (inevitably known as testicle scratcher), run by and attended by other art students doing their National Service; it was fairly anarchic, and a lot of fun.

When I left the army I took up a place on the teacher training course at Goldsmiths College in New Cross, London. From there it was easy to get into town to see plays, concerts, and exhibitions, a massive contrast to life in Yeovil. In those days the art magazines were printed in black and white, and the library at Yeovil Art School had been a glass-fronted cupboard, containing maybe 50 books. But the teaching at Yeovil was thorough. You were taught the essential skills of drawing, painting, and theory of colour. I was at Goldsmiths for a year, and learned a lot about art in general, then took a job at a secondary school in High Wickham for the year’s full-time teaching needed to complete my qualification.

After the year’s teaching, I went to France to see if I could make a living as a racing cyclist. However the French way of racing didn’t really suit me as it was very fast and furious, a lot of sprinting, and my forte was stamina, long distance racing up to 12 hours. So I travelled on down through Spain and met up with an old pal from Yeovil, Derek Boshier. I left my bike in Gibraltar, and we crossed to Morocco, hitching south to the Sahara. We drew, just using pencils and charcoal; and there was a moment, there in the Moroccan desert, when I clearly realised this was what I wanted to do. I thought it doesn’t matter what job I do as long as it’s undemanding and allows me to make art. So on returning to Montacute, I worked as a gardener, and produced some large paintings. With these I held my first successful solo exhibition in Bath. At the end of that year I decided I needed to go back to London, live amongst the art scene, and find a gallery. That was 1961; I worked in the evenings and painted by day, and was introduced to a very avant-garde gallery which showed abstract work from all over Europe—the New Vision Centre. I had two exhibitions there, in 1964 and 1965.

In 1966 I received a call from the head of printmaking at Brighton College of Art, a friend from Goldsmiths, offering me a job teaching screen printing. Initially it was only one day a week, but well-paid enough to allow me to continue painting. I took the job, and in fact carried on teaching at Brighton until I retired in 2001. I was always a painter who taught part-time, not a teacher who painted at weekends. I had a contract with an American dealer who sold large numbers of my prints in the USA. I continued painting and showing work, however, a recession meant it became hard to sell work, and I found I’d painted myself into a cul-de-sac, making paintings from pre-determined colour charts. I had the equivalent of writers block.

In 1971 I bought a cottage in Lyme Regis, and spent weekends and holidays here. West Bay was the social honeypot at that time, there were always parties on a Saturday night, and the Bridport Arms was so packed you’d never get a drink unless you knew someone by the bar. Of course London was amazing too at that time, the late sixties, and I was one of the first generation of working class kids who had benefited from further education, along with David Hockney, Peter Blake and Derek Boshier, all of whom I knew then and still do. Despite its attractions London was losing its appeal for me, and having sold our properties my then partner and I bought a small farm near Askerswell, where I reared sheep. Country life didn’t suit her however, so she returned to London and we sold up. The proceeds from that enabled me to buy Newhouse, which was derelict, but I needed a project and spent most of my time restoring it. Slowly I began to paint again, and in 1995 held an exhibition at the Meeting House in Ilminster, the first one in 20 years. I began to sell in London again, and through a gallery in St Ives, and my career grew once more.

Four years ago during Dorset Art Weeks a man walked in, who turned out to be an art dealer who knew everything about my past career. He was able to get me a show at the Redfern Gallery in 2014, which was a huge success and has made life comfortable for me. Over the years there have been many influences on my work. I knew from the word go I was never going to be an illustrator, so the work has always been abstract, imagined from influences as varied as Dorset archaeology to prehistoric rock art in Ireland and Brittany.

I’m have now completed a catalogue of my 64 years of paintings. It was published on the 12th August, my 80th birthday. The first book launch was at the Art Stable, Child Okeford on 17th September. My partner of 10 years, Jacy, and I live here in happy isolation, two artists with a beautiful view of the Axe Valley and Windwhistle Hill.’