The greatest global killer since the Black Death

As the First World War staggered towards its bloody conclusion 100 years ago this month leaving 17 million dead, the war-worn world suffered a second catastrophe. A lethal influenza pandemic swept the planet killing at least 50 million people. Most towns in the UK have fitting memorials to the war dead but the many who died from influenza are neither commemorated nor remembered. The Spanish flu, as it came to be called, was the greatest global killer since the Black Death. It is very important that its victims should not be forgotten and lessons learnt for dealing with future pandemics.

By June 1918, the fighting had been raging for nearly four years. Already worn down by the privations of war and the deaths of so many young men, people in the UK began to suffer the symptoms of influenza. Sore throat, headache and fever were typical but, after a few days in bed, people recovered and got on with life as best as they could. The illness had already swept across the US in the spring, reaching the trenches of the Western Front by mid-April leading to a brief lull in the fighting while troops recovered.

By September, however, a second wave of influenza surfaced, now in a deadly new guise. The virus was highly infectious sweeping through populations and quickly reaching most countries around the globe, its lethal progress assisted by the movement of troops to and from war zones. The majority experienced typical flu symptoms, perhaps a little more severe, and recovered quickly but, for about one in twenty of those infected, the effects were much more serious. Pneumonia-like symptoms caused by bacterial infection of the lungs were common leading to breathing problems and copious bloody sputum. Sometimes, the face and hands developed a purple-blue colouration suggesting oxygen starvation. This colour might spread to the rest of the body, occasionally turning black before sufferers died. Post-mortem examination revealed lungs that were red, swollen and bloody and covered in watery pink liquid; victims had effectively drowned in their own bodily fluids. There were no effective treatments, antibiotics had not been developed, and the death rate was high. By Christmas the second influenza wave had burnt itself out only for a third wave of intermediate severity to strike in the first few months of 1919. The pandemic came to be called “Spanish flu” because Spain alone, not being part of the war and so not subject to censorship, reported its flu experience freely.

In the UK, the Spanish flu killed 228,000 people in the space of about six months but this was a global pandemic and around the world the mortality was staggering. There were 675,000 deaths in the US and up to 17 million in India; overall the illness killed at least 3% of the entire population of the world. Unlike typical seasonal flu epidemics, deaths from Spanish flu were highest among 20-40-year olds with pregnant women being particularly vulnerable. If World War 1 had consumed the flower of youth, Spanish flu cut down those in their prime.

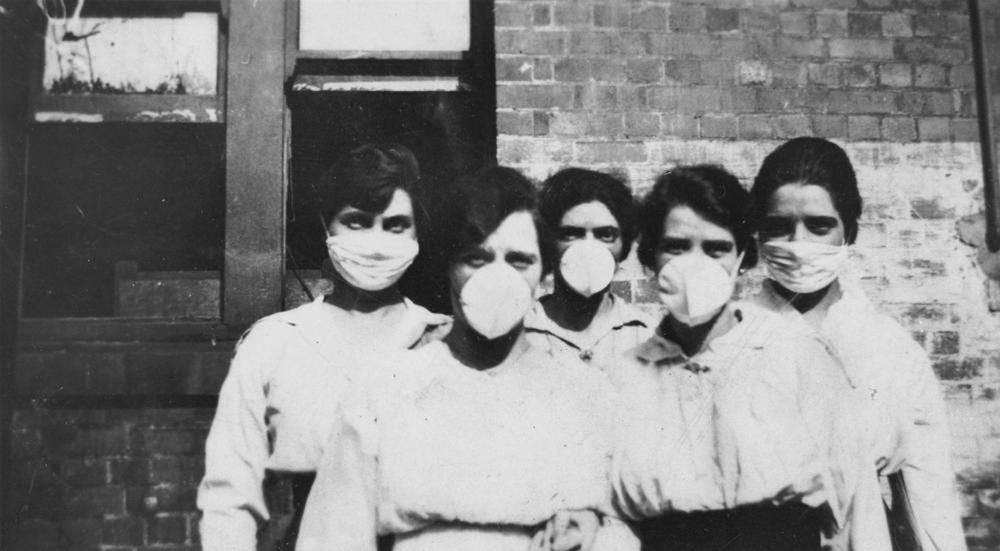

The sudden, widespread occurrence of a major illness with such high mortality caused huge disruption to daily life in the UK, especially in large towns. Medical services were overwhelmed as many doctors and nurses were on war service, funeral directors were unable to cope and there were reports of bodies piling up in mortuaries. The response of the medical authorities was poor, underplaying the gravity of the situation and providing little guidance; the newspapers, wearied by war news, were reluctant to give this new killer much coverage. Understanding of disease in the general population was rudimentary and a sense of fear and dread prevailed as people witnessed so many apparently random deaths.

In the West Country, the second wave of influenza killed at least 750 people in both Devon and Somerset and about 400 in Dorset but many thousands must have been unwell. Contemporary reports from Medical Officers of Health and local papers give some idea of how life was disrupted:

“In Lyme Regis, schools were closed for a fortnight in October 1918 as a large number of teachers, as well as children, were stricken down with the malady”

“The epidemic occurred when there was a great shortage of doctors and nurses across Devon and in the autumn of 1918 many cases succumbed before they could be visited; so bad was this in north Devon that, in answer to appeals from Appledore and North Tawton, two members of the School Medical Staff went to the aid of overtaxed doctors”

“Schools in Dartmouth were still closed in November 1918, social functions postponed and a Corporation soup kitchen opened to supply nourishing soup for invalids”

Given the high mortality and the disruption to normal society, I find it surprising that the pandemic was not commemorated and seems to have been forgotten quickly. Perhaps after four long years of carnage abroad and disruption at home, another horror was just too much, and the only way to cope was to forget?

But what was it about the 1918 flu virus that made it so virulent producing symptoms unlike any seen before and killing so many people? We still don’t know but scientists in the US have made some headway by studying the virus extracted from corpses of people who died during the second wave of the infection preserved in Alaskan permafrost. This showed, surprisingly, that the 1918 virus had a structure similar to a bird flu virus. This partly accounts for its virulence: its bird flu-like structure would have been alien to the immune system of people at the time. Because it also had the ability to infect human cells, it was a lethal vector of disease-causing, in some patients, severe damage to the lining of the respiratory tract leading to bacterial infection and pneumonia, engorged lung tissue and bloody sputum. A flu virus normally found in wild birds had acquired the ability to infect humans and the pandemic was the result.

Could history repeat itself? Could the world experience another lethal influenza pandemic? There is certainly concern among experts that this could happen and the Government recognises pandemic influenza as “one of the most severe natural challenges likely to affect the UK”. Current concern is focussed on two bird Influenza viruses circulating in the Far East. Since 2003, these have infected more than 2000 people and nearly half have died. Almost all the human infections have come from close contact with poultry or ducks but should one of these viruses change so that person to person transmission becomes possible, then we could be facing another major pandemic. How would we react? Our healthcare systems, at least in the developed world, are more sophisticated compared to 1918 and surveillance is better so that we should have early warning of the start of a pandemic. The UK Government has an Influenza Pandemic Preparedness Strategy, we have antibiotics and vaccines to combat bacterial pneumonia and some antiviral drugs to reduce flu symptoms. There is still the likelihood that healthcare systems would be overloaded and perhaps our best long-term hope is the development of a universal flu vaccine to protect against all strains of the virus.

Philip Strange is Emeritus Professor of Pharmacology at the University of Reading. He writes about science and about nature with a particular focus on how science fits into society. His work may be read at http://philipstrange.wordpress.com/