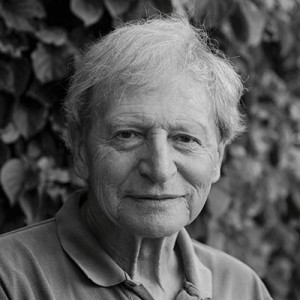

Fergus Byrne went to West Milton, Dorset, to meet Brian Jackman. This is his story. “I grew up in the Surrey suburbs but I always went on holiday to Cornwall every year. My dad worked for what used to be the Southern Railway, so he got privilege tickets, which meant while all my mates went to Bognor and Littlehampton, we could go all the way down to St Ives. And so I fell in love with Cornwall and the West Country. In fact there’s not a year of my life I haven’t crossed the Tamar. Then came the war. One night when I was five years old a bomb fell not so very far away and all the ceiling fell down on me in bed and I said, ‘Dad, was that a bomb?’ He said, ‘Yes it was, go back to sleep.’ In the morning I sat down in the kitchen to have breakfast and a delayed action bomb went off and blew the kitchen door across the room. As a result of that I was evacuated to a farm in Cornwall and I lived there for nearly two years. I never went to school. I used to milk by hand and plough with a heavy horse called Punch. We had water from the well, oil lamps and a bath in a tin tub in front of the range once a week. Then I went to Rutlish Grammar school in Merton which I hated because it was a rugby school. I just wanted to go to Epsom Grammar where they played football. They’d say ‘Jackman you’re playing for the school second 15 this afternoon’, and I’d say no I’m playing football for Wimbledon Juniors, and off I’d go. That was absolutely heresy then. We all dreamed of playing for England. My Dad took me and a friend to see Chelsea versus West Ham on a damp, misty, foggy London day, and warming up Tommy Lawton thumped this old fashioned muddy leather football against the crossbar and it just rattled. That was it for me, I was utterly hooked, that’s all I ever wanted to do. Not making it a career is my one bitter, bitter disappointment in life. However I resurrected my career late in life and played Sunday football for Powerstock—scored a couple of golden goals which I dream about even now. So I got my seven O-Levels and went off and became a Fleet Street messenger boy earning three pound ten a week. Then came National Service and I joined the Navy. It was a great leveler, you met guys from all over the place, Brummies, Geordies, Scousers, Glaswegians and the people I enjoyed best were the good old easy going west countrymen. One of my closest mates was a guy from Yeovil called Max Seaford, and he became the world’s most unlikely bank manager I think. The year I got out of the Navy I hitchhiked down, turned up at his door and his mother said, ‘Oh he’s not here he’s gone to West Bay.’ So off I went to West Bay, pitched up at Pier Terrace and there was a little note on the door and it said “this is the abode of Roger Courtney and Bill Snakebite Hitchcock, friends rings twice, girls walk straight on up.” So we’d go down and drink snakebite in the Bridport Arms and then lay out on the east beach and then go off to another party. Eric Hamblett, who eventually became the harbourmaster, used to sleep in the bath. I was allotted two armchairs shoved together to make a bed. I would go to sea with Rex Woolmington and Barry Hawker who owned a lovely old boat called the Peace & Plenty. I used to help them pull lobster pots and set nets for sea bass. So it became the start of a brilliant time with this wonderful crowd, a lot of whom I know to this day. Ray and Eva Harvey, Arthur Watson who I first met grilling mackerel over a driftwood fire on the Chesil Beach at an all-night party. And of course my great friend ‘Stu’, Ian Stewart—sublime boogie piano player and one of the original Rolling Stones, who was also a regular visitor to West Bay in the 1960s. Sadly a lot of them have passed away including Eric Hamblett. Around the same time I started a skiffle group called The Eden Street Skiffle Group. We played at the Royal Albert Hall, the Royal Festival Hall. There were three of us who played guitars and sang in harmony, one of them being Hamish Maxwell of Custer’s Last Blues Band. We used to come down with the group and play in pubs like the Bridport Arms. Hamish loved Bridport and West Bay as much as I did and he eventually moved down. And then I got married and bought a cottage in Powerstock for a few hundred pounds, you could still do it in those days. That was in the late 1960s. I’d managed to join The Sunday Times and became the lowest paid journalist on the paper but I didn’t care. I was so proud to walk in through this door which bore the legend of The Sunday Times. And so I became one of Harry’s children, Harry Evans the greatest editor ever. So they got me writing stuff on wildlife and conservation and that was the time when Kenneth Allsop was on TV most nights. Kenneth Allsop came to live down here at West Milton and because of a shared interest in bird watching we very soon became friends. He had a fantastic colourful turn of phrase which I was very strongly influenced by at the time. He became my guru both as turning me onto what conservation was all about and also the finer points of writing. It was only a couple of years later that he died, which was a dreadful wrench. He loved peregrines as I do and he never lived to see the peregrines return to West Dorset. Much as I enjoyed working in London I could hardly wait for Friday, when I would catch the train to Dorchester and then drive west, following the sun over the Roman road to Eggardon. For 30 years Eggardon filled my kitchen window, a billowing cloud of grassy limestone starred with flocks of grazing sheep. For me, its reassuring presence on the eastern skyline was a monument to Dorset’s enduring nature, shutting out the world of cities. Like Karen Blixen on her farm at the foot of the Ngong Hills in Kenya, I would wake every morning and see Eggardon and think—here I am, where I belong. I used to wake up in Powerstock to the sound of cows being taken down the road to milk, the clatter of hooves and the slap of cow pats hitting the tarmac. Travel took me all over the world—I was so lucky. I went to the Arctic looking for polar bears and to India to look at tigers, and I’ve been to the Pantanal, the Galapagos, skied in 60 different resorts all over the world. But Africa was always my big passion. Eventually The Sunday Times let me go there in 1974 and it just blew me away, and I saw my first lion. It was just stunning. And then very soon after that I got to meet Joy Adamson and after she was murdered I got to meet George Adamson at the funeral. I went with George to see his lions. He chucked some old camel meat in the back of the Land Rover and we drove down to the river. He called for a lioness called Arusha, like you would call for a Labrador, and this lioness came bounding up, blood all over her muzzle and she ran at George. I thought she was going to kill him but she just stood on her hind legs and draped her huge paws over his shoulder, and he just hugged her. She saw me and wandered over and her head filled the window. She was right next to my face and her breath smelt. How amazing it was. I went back again and stayed and spent quite a lot of time with George and we became friends until he also was shot dead by bandits, poachers. But I remained and still am a trustee of the George Adamson Wildlife Preservation Trust and a patron of Tusk Trust and all these things that you collect on the way, fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. And then, after I had known George, I met Jonathan Scott, the Big Cat Diary presenter. We wrote this book about lions called The Marsh Lions and it became a wildlife classic. In fact this year it was republished in paperback on the 30th anniversary of the original publication 30 years ago. I covered all the ivory poaching wars and tried not to get shot by bandits. In Tsavo National Park at the height of all the trouble, AK47 bullets whistled over my head, which was not fun, and finding these appalling carcasses of elephants with their tusks and their faces sometimes sawn off with a chainsaw—was absolutely dreadful. I still go to Africa two or three times a year and probably know the Maasai Mara more intimately than I know Dorset—it’s extraordinary. But I could never live anywhere else but here. My roots are here deep down. I live with my wife Annabelle. We’ve got a beautiful garden and this fabulous view that sums up everything I feel about West Dorset, the green West Dorset hills. I am surrounded by wildlife, badgers come and eat our carrots, we’ve got otters and kingfishers in the stream, the buddleia gets covered in Red Admiral butterflies. Annabelle has a donkey, an Exmoor pony, a beehive, two cats and nine hens. It’s the idyllic country existence and I’m either writing or gardening these days. I still write, I mean, why should I ever want to stop?”

Linking Environment and Culture. Reaching out to the wider local community and beyond

Contact us: info@marshwoodvale.com

© Marshwood Vale Ltd